TW. Graphic Imagery

The War.

Imagine a sunny day – children’s laughter bouncing high up on the Manila walls, parents busy with their mundane work, the lolos and lolas sitting on their sturdy Narra rocking chairs. The music of life fills the busy streets of Manila as everyone goes on their day. Its melody was like that of a radio broadcasting the city’s life.

Transcript in Filipino and English here (click)

Suddenly, static permeates the streets as if something eerie is fast approaching. Announcements are made across the city that the Japanese have arrived; this would be the genesis of a murder that would occur for almost four years.

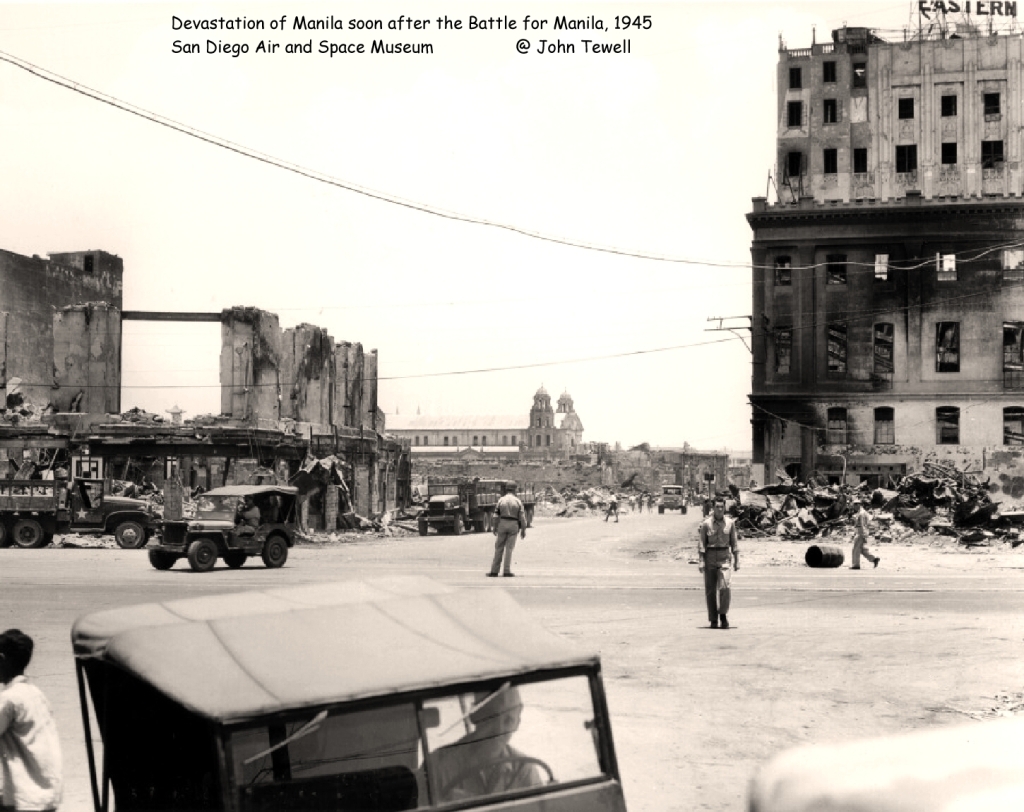

Flash forward to February 1945, the Battle of Manila would unfold, representing the clashing wills of Japanese brutality and Filipino-American freedom. It would go on to be one of the climactic chapters in the Pacific Theatre of War at a devastating cost – the city paid the price with its soul.

The month-long battle saw the historic city come crumbling as shells and bullets riddled the area. Chaos reigned, and fires ravaged everything in their path and destroyed buildings, the only remaining witness to Manila’s centuries of history.

(John Tewell, 1945)

The end of the battle would mark the closing chapters of the Philippines in World War 2. An estimated range of $0.8B-1.25B worth of damage to the Philippines (as of February 2024, it is worth $13B-21B), and more than 100,000 priceless people were killed. The Filipino people had regained their capital and freedom at the expense of its destruction.

Philippine War Damage Commission.

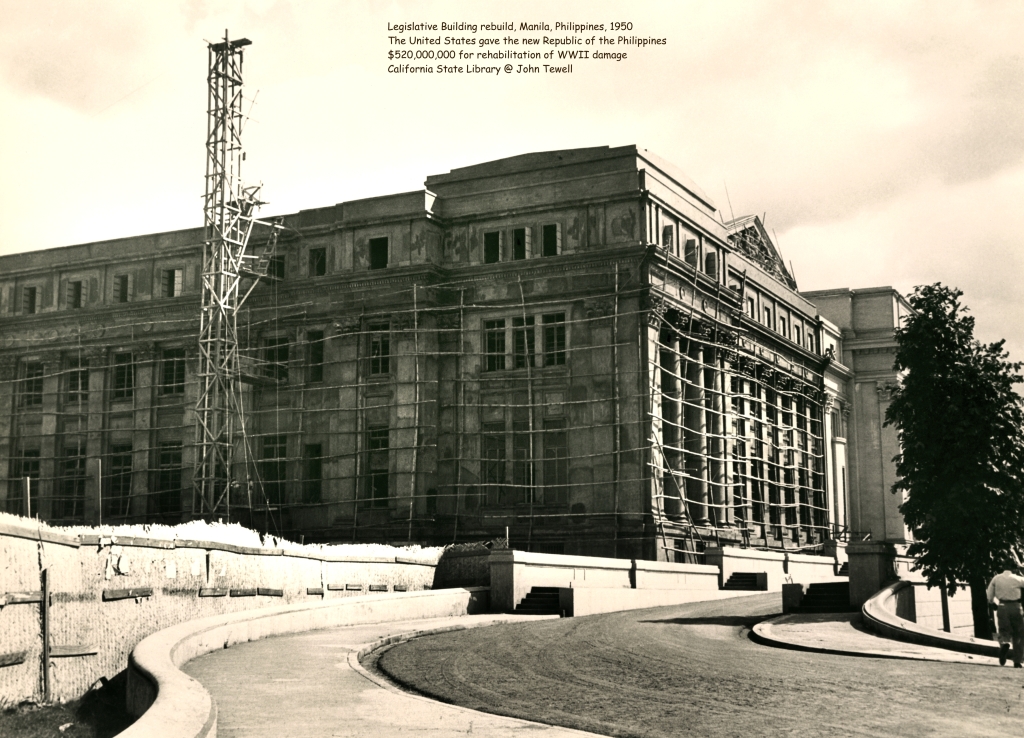

As early as 1942, US President Franklin Roosevelt’s voice rang defiant across the Japanese aggressors. He boldly declared to the Filipino people and American personnel that the Philippines would be liberated and rehabilitated. From every burnt bahay-kubo to every kalabaw killed, he swore that the islands would get each penny back.

His statements reintroduced the idea of war claims, once a rigid legal process, for the sake of national rehabilitation and humanitarian needs. The US would require the War Damage Corporation to settle any approved insurance claims before July 1942, through an Act of Congress. Despite this noble law, it was highly flawed due to the lack of control of the Philippines from Japanese occupation; insurance investigations would be a logistical problem.

The Philippine War Damage Commission Security Unit (Kahimyang Project, 2013)

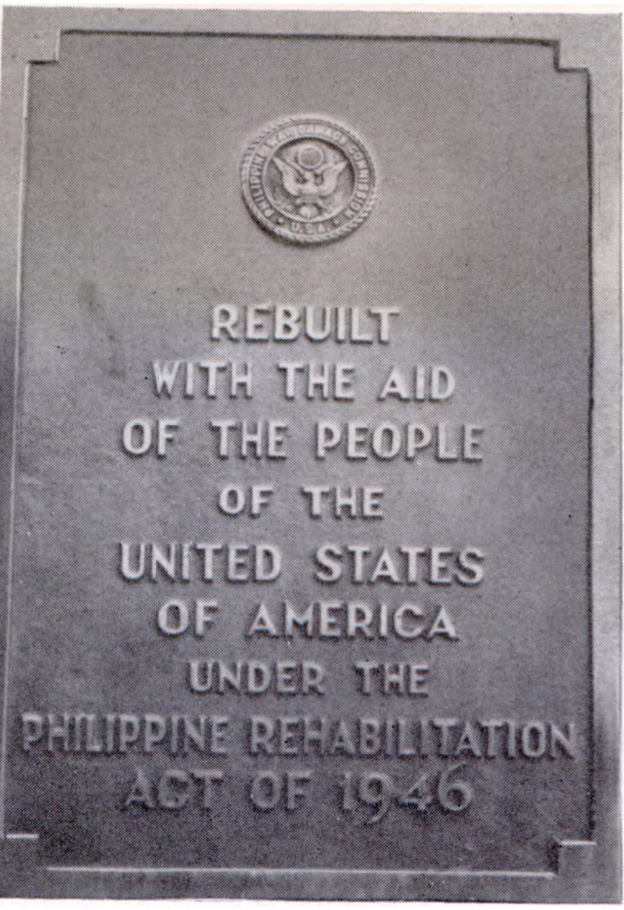

From back and forth in Congress, it was only after the Filipino-American victory in 1945 that the plan became tangible. Millard Tydings, an American champion of Philippine Independence before the war, proposed in November 1945 the Philippine Rehabilitation Act. Enacted in 1946, the law created the United States-Philippine War Damage Commission to investigate and facilitate payments for the destruction caused by the war headed by three commissioners. The sole Filipino Commissioner was Justice Francisco Afan Delgado who worked for the Court of Appeals. Alongside him were American Commissioners, Dr. Frank Warring and John Young meant to represent American goodwill. The three would go on to Manila and open its inaugural office by the end of 1946.

Francisco Delgado (National Library of the Philippines, Undated)

The Commission was given a budget of $388M for private claims and $12M for its operations, totaling $400M. They had a monumental task to oversee the allocation of their limited capital, and they needed to answer these three questions to operate efficiently:

- What were war claims, and which were compensable?

- How would they value such belongings when everything around them was destroyed?

- Who was eligible to receive such claims?

What Are War Claims?

World War Two unleashed death and destruction, offering no comfort to those caught in its crossfire. The harsh reality is that harms inflicted through legal military actions rarely come with compensation. However, evolving ethical standards changed the perception of what was to be repaired and what wasn’t.

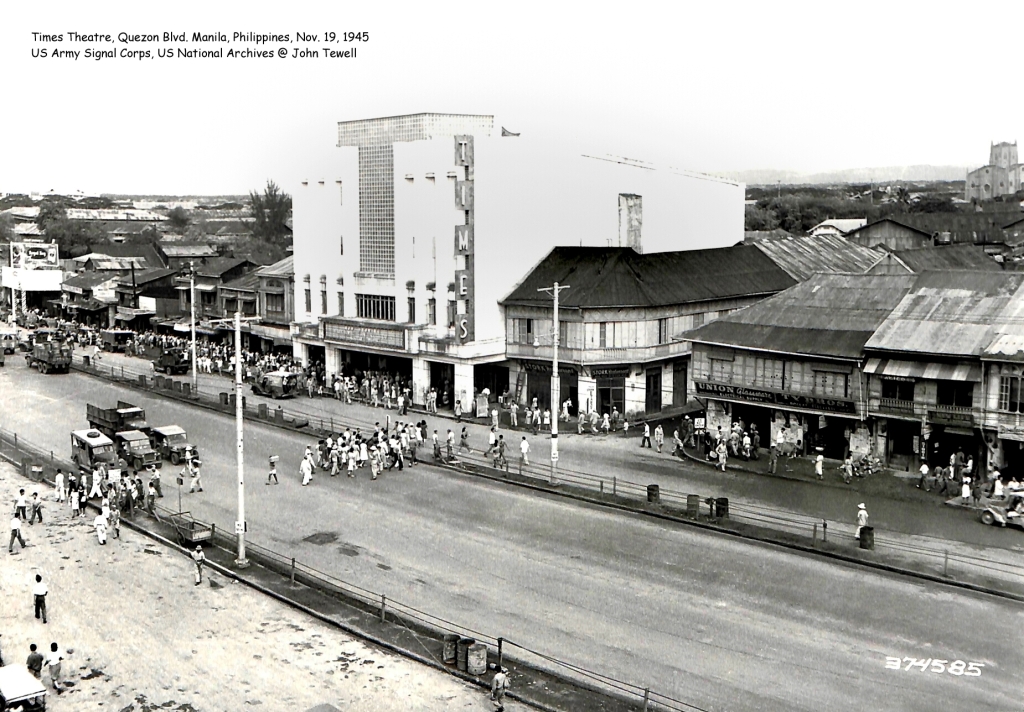

(John Tewell, 1945)

The Commission was not just counting pesos, it was upon them to weigh the story of each Filipino behind those claims, sift through the ashes of memories, and assign a nominal value. Enemy attacks, looting, and even military actions – each a different story, each a different value.

Quantifying grief and trauma was no easy feat as the Commission walked a tightrope having to balance compassion with practicality. At the time, defining compensability differed among the Philippines and America’s allies due to differing ethical standards and governmental priorities. Frequent legal consultations, physical surveys, and research were made to ensure the balance and identify the prime concern on rebuilding the Philippines.

(John Tewell, 1945)

Navigating through a complicated system of eligibility criteria, the final framework came upon the following: enemy attacks, actions by allied forces to prevent enemy access, and looting during periods of lawlessness – these were just some of the accepted reasons for war damage claims. Proving the cause often involved witness testimonies, official reports, and painstaking reconstruction of events.

Further provisions for claims based on torts, broken contracts, interest, and even loss of profits were added for businesses to become operational again. The Commission considered losses to private and public property, from homes and businesses to farm animals and personal belongings. However, certain exclusions existed, like intangible property (e.g., patents and licenses ) or excessive amounts of jewelry.

How to Value?

The Commission had two responsibilities: to be financially and operationally responsible, and to compensate victims fairly. To achieve this, they had to determine the value of eligible claims. However, valuing these claims was a complex process due to the volatile prices caused by the chaos of war. To streamline the process and ensure consistency, the Commission decided to base valuations on either the 1939 pre-war environment or the current cost of repair/replacement.

To use the 1939 pre-war environment, they developed depreciation tables, listing common items and their depreciation rate based on their expected lifespan. They then multiplied the original price by the depreciation rate to determine the value of the item

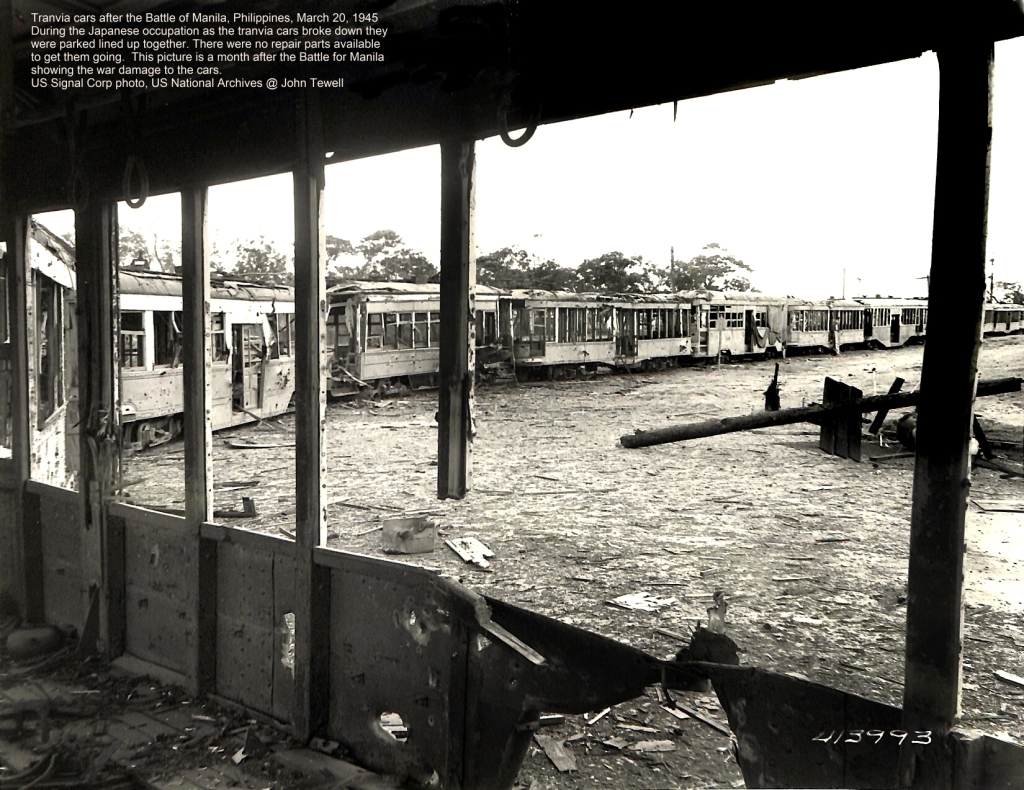

(John Tewell, 1945)

While these tables proved to be helpful in the overall process, there were drawbacks to them. Prices had risen since the pre-war purchase date leading to potentially unfair compensation. In addition, individual factors such as the condition or any special circumstance were not considered in the tables.

There were even plans to provide benefits by providing “restitution in kind” – or the return of lost property. However, this would be complicated as the chaos of war saw ownership documents burn in the flames. Looting was rampant as stolen goods would be bartered or sold to most likely purchase food. Restitution was not feasible as rebuilding everything from scratch would be a logistical problem. This forced the commission to weigh individual cases and consider factors that would render restitution.

Friend or Foe?

The Commission was not just about handing out funds but also about recognizing those who have never turned their backs on the Philippines. Ensuring fairness and preventing fraud was crucial. They had to astutely plan every move in establishing those truly eligible and ensure that enemies or collaborators would not profit. Reparations were only meant for those who deserved them—the people who had bravely endured the darkness awaiting their liberation.

(John Tewell, 1945)

By the Commission’s standards, qualified claimants included individuals, families, businesses, and even religious organizations that lost property during the war. Allies of these nations who had been living in the Islands for at least five years before December 7, 1941 were also eligible for claims. Included as well were those who fought for the Philippines and the American military who lost their property during battles. Each claim wasn’t just a number; it represented a broken home, a lost livelihood, and a community yearning to heal.

Where Did The Money Go?

Speed was crucial and ensuring legitimacy for war damage claims became a balancing act. Over 1.25 million claims flooded the Commission amounting to $1.225B – far from the $400M budget. While most claims were under $500, larger claims tended to be more tedious and more paperwork and investigation.

(John Tewell, 1945)

Among the initial beneficiaries were crucial pre-war institutions that formed the backbone of Philippine commerce. Public utilities such as the Manila Electric Company, the lifeblood of power supply, received compensation to restore their infrastructure. Similarly, transportation companies, both land and sea, were aided in connecting crucial paths for commerce to flow once again. Banks and insurance companies, pillars of financial stability, were equipped with fresh capital to secure confidence and facilitate economic activity. Even vital agricultural processing concerns like sugar and coconut mills, sources of livelihood for countless Filipinos, were supported in their revival.

(Philippine War Damage Commission, 1948)

Beyond infrastructure, the Commission recognized the importance of institutions nurturing the social fabric. Religious institutions, both Catholic and Protestant, played a critical role in education, healthcare, and community support. The Catholic Church, with the Manila Archdiocese leading the way, received substantial aid to repair damaged churches, schools, and social service facilities.

During the presentation of the Commission’s final report, they argued that larger claims that were disbursed triggered a fivefold economic boost generating $513M in increased income. They highlighted that targeted investment helped catalyze broader economic recovery.

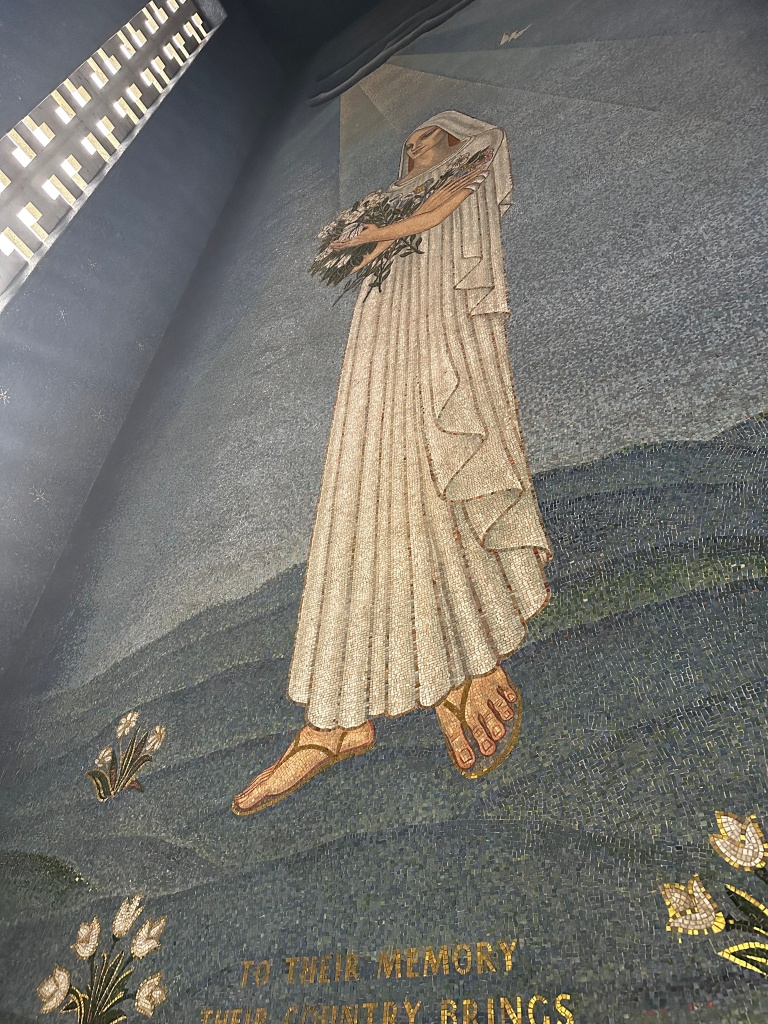

Me.

The idea for the article came to me during a trip to the Manila American Cemetery. Looking around, I found myself across the great Madonna in a chapel at the center of the cemetery. She was shrouded in white and surrounded by blue as if she were a guiding light leading souls back to the heavens.

Madonna (Raphael Canillas, 2023)

Standing there was an ethereal silence and solemnity for those who have fought for the Philippines’ liberty. A beam of light would radiate from somewhere showing the full beauty of the Madonna and along with it came my idea to pay tribute. Lest we forget the sacrifice of those who fought and rebuilt our nation.